- Joined

- Oct 7, 2023

- Messages

- 7

- Points

- 3

Question -

When did the shape of ship deadeyes change from triangular to round, and why

When did the shape of ship deadeyes change from triangular to round, and why

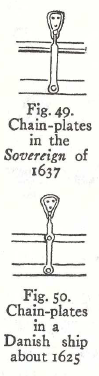

All good information! Also keep in mind that a single vessel may have been rigged a certain way and then re-rigged differently. As far as the change to round, I hypothesize that there was a change in technology, e.g., someone or some group developed a lathe-like machine that made it easier and quicker to make a round deadeye than a triangular one. Fair winds!Triangular deadeyes go back to the 16th century and as far back as the 12th century. Triangular deadeyes were phased out in favor of round ones in the mid-late 17th century. Here are a few examples ships that had triangular deadeyes. There exist deadeyes which are transitional between triangular and round, where the corners are rounded over more that the early deadeyes. Which style was used by which nation at which time is very difficult to see trends in because features like this were affected by trends, but many ships often broke common trends in design and features. If data is available, it's easy to determine the style of ship features such as deadeyes, or capstans, or the color of wales, etc. But, when we don't have data one a specific ship we are modeling, all you can do is try to use a trend in style to act as a guide in a feature, and hope it is correct. It may not, because of the exceptions I mentioned previously. Whn choosing the shape of deadeyes in the 1640's-1660's, you may have to guess because your ship of choice is in the transitional period.

As for the strength of design between triangular and round, the change may have come about because of ease of construction, or a discovery that wood is stronger in the round shape, in addition to a change due to style. Other members may have more information on this.

I am not a mechanical engineer but I would think the round deadeye was found to handle the stress better than the triangular one.Thank you, Uwe -

But to get back to the original question: why did the shape of ship deadeyes evolve from being triangular to round? Maritime industries follow conservative business practices so the change in my opinion seems rather rapid.

My guess is that with the advent of lathes, round is much easier and more efficient shape to deal with than a triangle. A billet could be put in the lathe. Holes bored along the length of the billet. Rope groves added along the length, font and back side radius formed and a block parted off progressing to the next one.Question -

When did the shape of ship deadeyes change from triangular to round, and why

I am not a mechanical engineer but I would think the round deadeye was found to handle the stress better than the triangular one.

This lead me to start thinking of the internal forces of physics (a course I barly got through in high school) There was something about the internal strength of cylindrical forms. The wheel comes to mind.

Thank you AndyI haven't analyzed the mechanics of a deadeye but I am skeptical of that hypothesis. Spherical and cylindrical objects certainly have some advantages in mechanical properties but these are typically of benefit when the stress is uniform and the material of the object is isotropic, that is, it has the same strength in every direction. An everyday example of a cylindrical object is a water pipe. The pressure of the water is evenly distributed on the inner wall of the pipe and the metal of the pipe has approximately the same yield strength in every direction. A system made up of a shroud, a deadeye, and a lanyard is more complex and there are various stresses in various directions on different areas of each of the components. Also, wear is a significant factor in rigging. So, the shape of the deadeye effects not only the strength of the deadeye but the performance of other parts of the system. If any of the components fail the system will fail. And, as other members have pointed out, wood is anisotropic; its yield strength varies in different directions. I'd say that determining the optimum shape and grain orientation of a deadeye would require significant (but perhaps fun) research. As in (almost) all things, economics and time also come into play. The optimal solution may give way to an acceptable solution that is easier and/or quicker. Shipbuilders and ship's carpenters of old depended on over-design and redundancy; make it stronger than you think it needs to be and use more than you think are necessary. If it breaks, make the next one stronger.

Fair winds!

Thank you M. HockerDeadeyes were round long before they were made on lathes (as Pebbleworm points out, lathes have been in use for thousands of years), although I am not sure when the transition occurred, there was doubtless some overlap between carved and turned round deadeyes. The carved ones usually have convex faces, the turned ones are more likely to have flat faces. In 17th-century Swedish shipyards, the people who made blocks and deadeyes were called turners (or turner blockmakers), although the only rigging items they turned were sheaves and parrel trucks. Blocks and deadeyes were carved.

The critical strength issue is probably not in the deadeye but the rope. The rope expert, Ole Magnus, believed that the round form was adopted because it put the most even load on the shroud, thus weakening the rope as little as possible. Bending a rope around an object weakens it, so the rope is most likely to break at a knot or an attachment to another object. The radius of the bend relative to the diameter of the rope is critical, with a larger radius causing less weakness. To prevent breaks, the rope has to be larger in diameter than the actual dead load on it requires. Reducing the amount of weakening means that a smaller, and thus lighter, rope can be used.

Part of the transition from the drop-shaped to heart and then round deadeyes was that deadeyes became wider for the same diameter of shroud (thus a smaller radius for the bend in the rope). They also became thicker relative to their diameter/width, which would have a beneficial effect on the lanyards, reducing the effective radius of the bend at each turn.

If anyone is interested, a recent discovery of a mid-14th-century cog in Varberg, Sweden included two lower shrouds still attached to the ship with drop-shaped deadeyes and lanyards. These had two rows of holes, and the lead of the lanyard did not follow the later rule. Olof Pipping has written a report.

Fred